PEACE: Armistice Day, 11 November 1918

On 11 November 1918, the Armistice was signed at 5.00am, in a railway carriage in the Forest of Compiegne, about 60km North of Paris, by representatives of France, Great Britain and Germany. It stated that fighting would end at 11.00am on that day. The terms of the Armistice required the Germans to evacuate German-occupied territories on the Western Front within two weeks, and all German-occupied territories elsewhere to be abandoned. A lot of German military equipment was lost, including its entire submarine fleet, and Germany had to pay reparations of around £59 million, which were only finally paid off in 2010. The Armistice initially ran for 30 days, but was regularly renewed until the formal peace treaty was signed at Versailles the following year.

Until 11.00am, however, for the soldiers it was just another day, and 863 soldiers died on the 11th November itself, but Capital cities began celebrating as soon as they heard the news. All over the world, people were celebrating, dancing in the streets and drinking, but at the Front there was no celebration. Many soldiers believed the Armistice was only a temporary measure and the war would soon go on. Many of them suffered complete nervous collapse after the months of intense strain.

Britain went wild with delight – all over the country, church bells were rung, business was suspended and houses were decorated with flags. In London, bands paraded the streets, and at Buckingham Palace, everyone was shouting ‘We Want the King’. George V duly appeared, and later drove through the streets with Queen Mary. That night, lights went on again for the first time since 1915.

Every year, starting in 1919, Great Britain has held a two minute silence at 11.00am on the 11th November, as a chance for people to stop and remember the 20 million who died during the conflict.

When the troops returned home, thousands lined the streets to welcome them in a series of Victory Parades.

Owing to an outbreak of influenza on board their ship on the voyage to England, the Indian contingent could not arrive in time to take part in the July Victory Parade celebrations and so a second procession was taken out especially for them on August 2nd. For four years, Indian soldiers had served steadfastly and made sacrifices on various fronts in Europe, the Middle East and Africa. Now, thousands of members of the British public lined the route from Waterloo to Buckingham Palace to see the officers and men of the Commonwealth who had fought in the war to protect them. King George V took the salute and thanked the troops for their magnificent services and loyal devotion.

Medals and Awards

Campaign medals were awarded to a person if they took part in a military campaign outside of the UK in a time of war. Some of these were given for particular acts of gallantry or service.

The Victoria Cross (V.C.) was the highest level of medal available. It is a medal open to all ranks, and is awarded for an act of outstanding courage or devotion to duty in the presence of the enemy. 615 were awarded during WW1 and a quarter of these were awarded posthumously. There were also several other gallantry awards, including the Distinguished Service Medal (D.S.M.) and the Military Medal (M.M.).

The other way in which soldiers were often honoured for bravery was for them to be Mentioned in Dispatches (M. I. D.). This is when an individual is mentioned by name for an act of gallantry in an official report written by the senior commander of an army in the field.

All those who received one of these awards are entitled to use the letters in brackets after their name, much like we would for a degree or diploma.

6.5 million British War Medals were issued. Also known as ‘Squeak’, they were awarded to everyone who had served overseas.

The 1914 Star and the 1914-15 Star were issued to those who served in the war on those dates. They were also known as ‘Pip’!

The Victory Medal or Allied Victory Medal was known as ‘Wilfred’. Around 5.7. million were issued. Each of the allies had a copy of this medal with an identical ribbon and translated wording.

Indian Army soldiers won 9,500 medals in France and Belgium, East Africa, Mesopotamia, Egypt and Palestine, and Gallipoli (they won a further 3,500 medals in India and in the frontier wars), including 11 Victoria Crosses – the supreme award for valour.

Returning Home

Returning soldiers found a Britain of high unemployment, strikes, a rising cost of living and a severe shortage of houses. They were initially given a month’s paid leave, then six months of small unemployment benefit before they had to join the dole queue.

For many returning soldiers, it was difficult to find work. Women had taken on a lot of men’s jobs, and many men found it almost impossible to readjust to civilian life. There was an upsurge in violence and drinking, and those who had fought became known as ‘The Lost Generation’.

In India, certain improvements were made for military personnel of the Indian Army who either remained in service at the end of the war, or who those who had retired and qualified for pensions.

- Honorary King’s Commissions were granted to Indian officers who had distinguished themselves in the Great War. King’s commissioned Indian officers had authority over British troops, which allowed them to command white troops, a situation not previously permitted for Viceroy commissioned Indian officers.

- Two hundred special jagirs (hereditary grants of land as a reward for service to the government) were awarded to some Indian officers in recognition of their distinguished services during the war.

- Twenty-thousand other rewards, consisting of grants of land or special pensions were also bestowed.

Disabled Ex-servicemen

From 1915, the state began providing a pension for ex-servicemen. 2,414,000 men who were wounded, and, as a result, disabled, were discharged and received a war pension of a maximum of 25 shillings a week and a silver War Medal. Initially, the amount provided was based on the loss of earning ability caused by the disability. However, this led to problems rehabilitating ex-service men, as they feared they would lose their pension if they went back to work, so it was later changed to a fixed amount.

Medical care was varied. If they had lost a limb, the soldiers were entitled to help from the state. However, there was a lack of state provision and sympathy for less visible injuries such as shell shock and internal injuries from gas and it was much harder to get a pension if you were suffering from disease or shell-shock. Although men who had lost limbs were popularly seen as heroes, there was little understanding of mental illness. As a result, voluntary services, such as the Red Cross, stepped in and organised specialist centres for the treatment and rehabilitation of shell-shocked men.

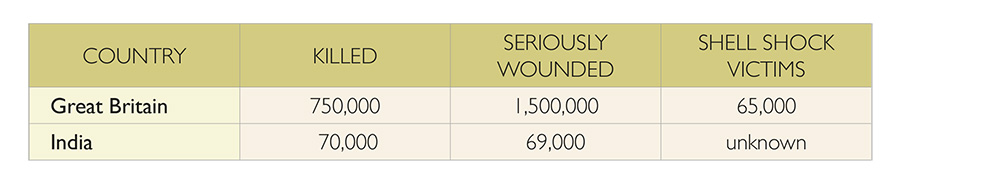

World War 1 in statistics:

According to one estimate, 30.58% of all men aged 20-24 in 1914 were killed, and 28.15% of those aged 13-19.

Despite the war ending in 1918, many men did not get home until well into 1919.

DESIGN AND TECHNOLOGY ACTIVITY 2

RELIGIOUS EDUCATION ACTIVITY 1