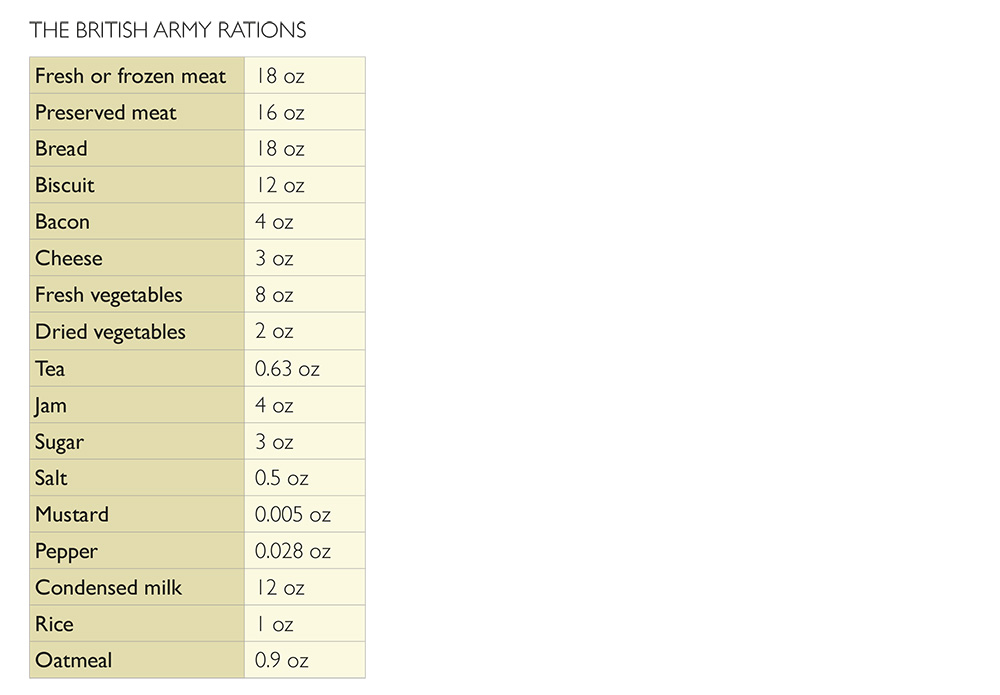

Food in the trenches of the First World War was scarce. Hot meals were considered a luxury, particularly at the front, and food was carefully rationed. The daily food ration per soldier worked out as follows:

In practice, field kitchens cooked huge quantities of food using these ingredients to be divided up amongst soldiers whether or not they were in the line. Sometimes, during an attack, for example, this was impossible, so soldiers carried ‘iron rations’ of tinned beef, stew, biscuit and jam. British soldiers rarely complained about going hungry, but they did complain about the monotony of their diet. The easiest food to produce in scale was stew, so stew was almost invariably what soldiers got! Parcels from home which supplemented soldiers’ food with items like biscuits and chocolate were therefore particularly welcome!

A Field Kitchen – Although they resemble some kind of field artillery, these are in fact field kitchens (the long pipes are the chimneys) destined for the front, and every bit as important.

© National Army Museum

To relieve the boredom of rations, ration parties would try and bring hot rations at nights, but they didn’t always arrive safely:

The rations’ carriers was a most unenviable task, as thankless as it was dangerous. Rarely in those days did they complete their double journey without casualties. Occasionally the whole party was wiped out while the company waited, parched and famished, for the water and food scattered about the mud and shell-holes. Water was more precious even than victuals. It was everywhere ‘but not a drop to drink,’ while the full petrol tins were cruel burdens to shoulder over a mile or so of battle-field.

Lt Sidney Rogerson, West Yorkshire Regiment

Dietary issues for The Indian Army

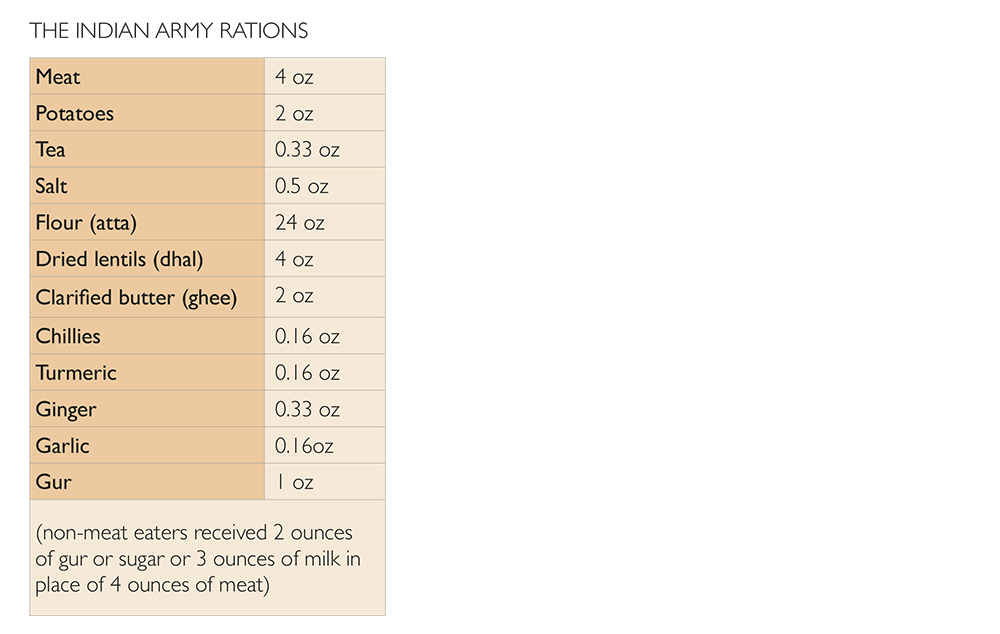

Diet was a sensitive issue for Indian soldiers and a complex logistical one for the British military authorities.

Muslim soldiers were typically meat-eaters. They ate most animals, such as beef, lamb, chicken or mutton, but not pork. Due to religious reasons, the animal had to be slaughtered in the correct fashion so that it was considered halal (permissible).

While many Hindu and Sikh soldiers were vegetarian, others ate meat such as pork, lamb, chicken or mutton, but the animal had to be killed in the jhatka fashion (i.e. decapitation with the single stroke of a sword). They refused, however, to eat beef on religious and cultural grounds.

Caste was another complication that meant that soldiers of certain castes would not eat or drink with those deemed ‘impure’. Cooks and their kitchens therefore had to be carefully selected so as not to offend the soldiers’ religious and caste-based sensibilities.

While there was no official vegetarian option for British troops, provision was made for Indian soldiers. This included mixed spices of ginger, turmeric, chillies and garlic, lentils (dhal) and wheat flour (atta). Instead of meat, vegetarians received additional cane sugar (gur) or milk.

The typical list of ingredients was as follows:

In the most extreme circumstances, some Indian soldiers were persuaded to eat their horses and mules in order to survive (e.g. during the siege of Kut al-Amara in Mesopotamia, (see Chapter 18), which lasted for over 140 days).

DESIGN AND TECHNOLOGY ACTIVITY 6