What is a Trench?

British armies have used trenches to protect their soldiers, usually when besieging towns, for centuries. What was different about the Western Front in the First World War was the scale. French, Belgian and British troops occupied a complex system of trench networks that ran from the Channel to Switzerland. At different times the BEF held between 25 and 123 miles.

Trench systems evolved over the course of the war as military thinking changed; and their exact construction depended on factors like the type of soil and the level of the water table. In general, any one battalion was expected to occupy three trench lines, one behind the other. At the front was the fire trench, the first line of defence and the jumping off point for attack. Behind was the support trench, a second line of defence, and behind that the reserve trench, from which troops could be sent forward in an emergency. The three lines were connected by communication trenches.

Trenches were built in dog’s tooth ‘fire-bays’ and ‘traverses’ rather than long, straight lines, to make them harder to attack. Ideally a ‘good’ trench was deeper than head height, and had a ‘fire-step’ that allowed soldiers to see and shoot over the parapet. The base of the trench might have slatted boards to make it easier to walk when wet.

Instructional diagram of a Fire Trench, with a Supervision Trench behind it, mainly to allow officers to move quickly from one part of the line under their control to another.

© National Army Museum

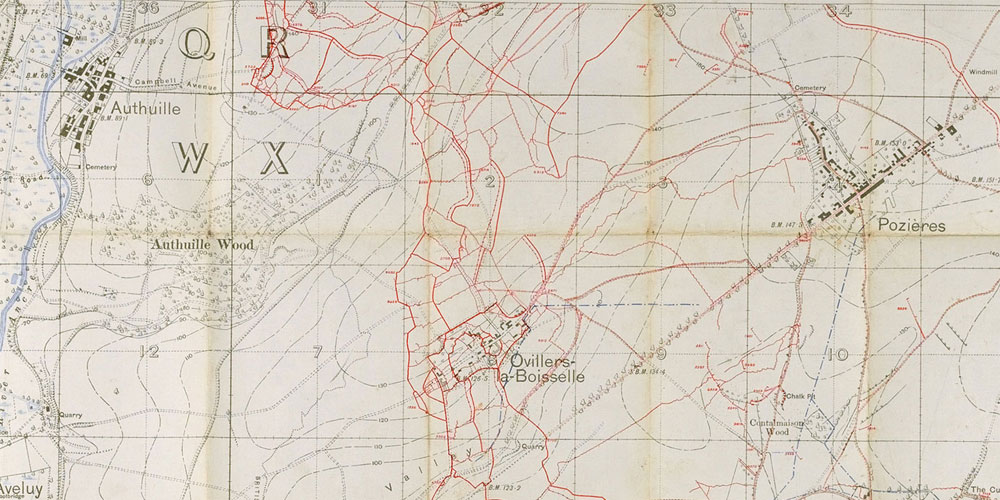

Trench map, belonging to war poet Siegfried Sassoon. The red trenches are German – British trenches aren’t shown in case the map falls into enemy hands, but they follow a similar pattern.

© National Army Museum

The Trench Experience

If you want to find the old battalion,

I know where they are….

They’re hanging on the old barbed wire,

I’ve seen ‘em, I’ve seen ‘em hanging on the old barbed wire.

Soldiers Song 1916

A soldier’s battalion did ‘tours’ of trenches, which usually lasted a couple of weeks. One battalion was divided into four companies, each of about 160 men. When a battalion was allocated a section of trench, two companies guarded the fire trench, with one in support and one in reserve behind them. The companies would be rotated during their ‘tour’ so that no one company was in the fire trench for more than a couple of days at a time.

It is up to eyes in mud out here, I don’t know what you would say if you could see me now sat in a hole in the railway bank with a couple of old sheets of corrugated iron over it to keep the rain off, and my clothes covered in mud. But we have got a fire so we think ourselves lucky.

Pte Herbert Dando, 1st Battalion, The Queen’s (Royal West Surrey Regiment)

The daily routine in ‘tours’ of trenches was predictable. Most activity happened at night when, under the cover of darkness, soldiers repaired trenches and barbed wire defences, or dug new ones; crept towards enemy lines to gather information; or even launched local trench raids to take prisoners for questioning or just to keep the enemy guessing. In the day, soldiers slept, ate, and wrote letters home. Sentries were posted all the time, but at dusk and dawn, the most likely times for an enemy attack, the whole battalion had to ‘stand to’, clambering up onto the fire step to keep watch. Once the battalion had completed its ‘tour’ it would be brought out of the line to rest, re-equip and re-train. This might take a few weeks, then the battalion would be sent back to the front.

Soldiers Eating – In the day time soldiers slept and ate. In the photo above, it looks as though soldiers are sharing fresh food sent from home to supplement their rations. The large clay bottle is a rum jar.

© National Army Museum

If launching a big attack everything changed. Dozens of infantry battalions massed, sometimes weeks beforehand, with Engineers, Signallers, Service Corps and of course Artillery. After an Artillery bombardment, waves of infantry left the relative safety of the trenches to try and take enemy positions. The waves were intended to leapfrog each other. Once the attack was over, if enemy trenches had been taken, they would be converted and reinforced, and the routine of ‘tours’ started again.

From all sides darted flashes of brilliant fire, a perfect aurora of flame, silhouetting squat bushes, shattered tree trunks and pock-marked fields gleaming with water. In the sky gleamed dozens of brilliant blue lights, varied by showers of lovely golden balls.

Pte Arthur E Lambert, 2nd Battalion, Honourable Artillery Company

My dearest John, Thank you so much for your beautifully written letter which came to me here in the trenches. I am living in a little cave just behind the trenches. They call it a dug-out, and it is very like a rabbit’s burrow. Every now and then I go through a little passage into the trench to have a look through a spy-hole at mister German, but he is very careful and does not show himself much, as he is frightened Daddy might shoot him.

Col Ruddles-Brise, Essex Regiment, writing to his son, 11 February 1915

Soldiers sometimes scraped out what they called funkholes (to be funky was slang for being scared) in the forward face of rear trenches for extra shelter.

I noticed as I passed along that the trenches were not only beginning to look more efficient as defences, but more lived in, more ‘homely’. German bayonets stuck in the walls served as pegs for bandoliers of cartridges, water bottles, and other parts of his complex harness which Mr Atkins was accustomed to take off in the trenches. Here and there hung a gas-gong in the shape of a brass shell-case.

Lt S. Rogerson, West Yorkshire Regiment, 1916

Troops waiting for Action. The constant movement of troops from one place to another meant that soldiers had to do a lot of waiting around.

© National Army Museum

The Daily Routine of life in the Trenches

Watch this film to get an idea of how life was for the soldiers in the trenches:

Click here for more detail on life in the trenches.

Indian Soldiers in the Trenches

It is likely that in virtually all theatres of war, Indian soldiers sang and indulged in their national sport of wrestling. During their time on the Western Front, Indian soldiers also played football, competed in tug-o-war matches and competed in running events. More unusual activities practiced on a smaller scale were tent-pegging, fishing (with lances as rods) and water-barrel races.

MATHEMATICS ACTIVITIES 4, 8 AND 9